History | National Geography

Vineyards | Origin protection

History

There were vines in the Tokaj wine region in ancient times. This is evidenced by a fossil found in the Erdőbénye area in 1867, which became known to the world as Vitis tokaiensis. It was probably only in the 9th century, with the arrival of the Hungarians, that grape cultivation began in earnest, as the conquering Hungarians were already familiar with wine as a beverage and thus also with its raw material, grapes. The name “Tokaj” itself probably derives from the Kabar people who settled here. However, the first written reference to the area appears in Anonymus’s work Gesta Hungarorum, estimated to have originated at around 1200, which mentions the connection between Tokaj and grapes. There is also evidence from the early 1200s that “foreign peoples” lived in Potok (Sárospatak) and its surroundings, but it only became clear in King Béla IV’s charter of 1252 that they were winegrowers, as he referred to them as “vinitora.” These people, mainly of Italian origin, combined the knowledge they brought with them with the local knowledge of cultivation. There are continuous written records and evidence of Tokaj wine trade dating back to the 14th century. The first mentions of vineyards such as Királyhegye (1338), Megyerhegy (1342), Mézesmál, Tarcal and Tokaj (all 1434) also appeared in this century. Transport routes for the Hungarian wine trade had been established by the end of the 15th century. Wine was mainly transported to Poland via Košice (Kassa), but the most popular Hungarian wine was still the strong, sweet wine from Syrmia (now is Serbia).

In 1521, the Turks ravaged Syrmia, destroying its vineyards and putting an end to its wine trade. As the Turks advanced northwards, the Baranya and then the Tolna growing regions took over the supply of demand, but this did not last long either. Tokaj gradually reached the point where the style and quality of its wines, as well as the commercial conditions, created the constellation necessary for its rise. However, proof of the quality of its wine can also be found in the 1530 work of Paracelsus, a Swiss physician who visited Hungary in 1524 and recalled Tokaj wines at the highest level, calling them liquid gold.

However, the real breakthrough was unquestionably the emergence of Aszú. This was undoubtedly the result of several steps, with historical circumstances also playing a role in this. There have always been some aszú berries in Tokaj in favourable vintages. As is commonly known, aszú berries develop when noble rot sets in at a high sugar level; otherwise, the berries simply rot. We can rightly assume that such fortunate cases occurred relatively frequently, but two things marked a shift in this. The first is that summer tillage to promote ripening became common in the 1500s. This led to riper grapes, which in turn increased the chances of botrytisation. The other event is now history. Tokaj Castle was besieged in September 1566 (amidst a complicated political situation involving the Turks, Hungarians and Transylvania), during which, of course, there was no question of harvesting grapes. The late harvest may have led to recognition of its favourable timing. Whatever the case may be, the first written evidence appeared in May 1571 in the form of a letter of donation from the Garay noble family, in which they gifted each other dozens of barrels of “Aszú” wine.

The Furmint grape variety also appeared in Tokaj at the beginning of the 17th century, but the circumstances surrounding this remain unclear to this day. Several records from this period have been found, but all they reveal is that the variety does not cope well with rainy weather.

In 1655, the national assembly regulated the production of Aszú by law, the most important part of which was that tax would not have to be paid on vineyards that had previously been subject to taxation. As a result, the production of Aszú increased and trade reached unprecedented levels, marking the beginning of the golden age of Tokaj wine, with 20,000 barrels of wine passing along the wine route in 1714. The foreign policy ambitions of the Rákóczi War of Independence in the early 18th century were aided by the gifting of Aszú wines, which promoted Hungarian wines in many places. Thus, thanks to a political agreement with Tsar Peter I of Russia, Russian exports also began to grow, and this trend continued even after the defeat of the War of Independence. The Tokaj Russian Wine Purchasing Committee was established in 1733 and mainly supplied Tokaj wines to St Petersburg. The Committee remained in the wine region until 1798.

This boom was interrupted by poor harvests in the 18th century, yet business success also led to an increase in wine counterfeiting. A royal decree defining the boundaries of the wine region and introducing many other provisions regulating trade and production was issued on 11 October 1737 to prevent this. The regulation established the world’s second system of origin protection (the first being Chianti in 1716), of which Tokaj and Hungary are justifiably proud.

However, the 18th century was not an easy period for trade. Poland came under Russian influence, new customs regulations came into force and many Aszú wines remained unsold, and it was impossible to break out of this situation even at the beginning of the 19th century. The end of the 19th century brought another blow not only to Tokaj but to the whole of Hungary: the arrival of phylloxera. Reconstruction began slowly but reached its most intense phase between 1904 and 1906, so that by 1911, the Tokaj wine region had more than 8,000 acres of planted land, most of which was modern for its time, laid out in rows.

Despite all this, trade was unable to return to its former level. The outbreak of World War I in 1914, followed by the Treaty of Trianon in 1920 (in which Hungary lost two-thirds of its territory), had a tragic impact. Trade routes disappeared and markets moved beyond Hungary’s borders. Poor harvests and the global economic crisis in the 1920s further exacerbated the situation.

Life in the wine region was turbulent until World War II, with periods of minor upsurges followed by more difficult times. Then everything changed in 1945, and the “new order” buried the wine region for more than 40 years. The Tokaj-hegyaljai State Farm Wine Kombinát (the legal predecessor of Tokaj Kereskedőház and then Grand Tokaj) was established in 1950. The main target of trade became communist countries, primarily the Soviet Union, and the demands of mass production slowly but surely also destroyed the product itself.

After the fall of communism in 1990, a new structure gradually emerged, from which the wine region greatly benefited. The first private producers appeared, who gained first national and then slowly international fame. Privatisation began at the start of the decade, during which several modern wineries with international capital and a different approach began operations. An agreement was concluded with the European Union in 1993, which stipulated the protection of places of origin. The names Tokay d’Alsace and Tocai Friuliano were discontinued with a derogation lasting until the 2007 vintage. The wine region became a World Heritage Site in 2002. A new wine law came into force in 2004, which reserved the production of Aszú exclusively for Tokaj, while also changing the name of the wine region from the Tokaj-hegyalja Wine Region to Tokaj. Its designation of origin was established in 2012 and still defines the professional life of the wine region.

Natural Geography

The Tokaj wine region lies on the northern border of grape cultivation, meaning it is located on the same latitude as Burgundy. Its relatively cool climate means an average annual temperature of 9-10°C, with precipitation of 5-700 mm. The wine region’s uniqueness lies in the influence of the rivers, as the autumn mist from the Bodrog and the Tisza is essential for botrytisation.

The wine region’s terrain is also extremely important. The most significant factor is that the Carpathian Mountains are very close here. The Zemplén Mountains are their final foothills and protect the region from the north, continental winds. Moreover, the region also benefits from the warm air coming from the Great Plain, which plays a decisive role in ripening the grapes.

The wine region stretches from southwest to northeast, forming a V shape. The tip of the V is Tokaj Hill (or Kopasz Hill), whose volcanic cone dominates the landscape. This is where the wine region meets the Great Plain, so the vineyards here behave very differently from the rest of the wine region.

The wine region can be divided into six areas in terms of topography: Tokaj and its surroundings, the Mád Basin, the Erdőbénye Basin, the Tolcsva Basin, the Sárospatak Basin and finally Sátoraljaújhely (Sátorhegy). Examined separately, these basins are quite similar in that they form a new V shape perpendicular to the main V shape. This means that the basins are open to the warm air and humidity coming from the Bodrog River, which also mixes with cool winds coming from Zemplén. This process creates a special microclimate that adds another level of diversity to the wine region.

However, Tokaj’s most important characteristics – and thus the final level of diversity – can be found in its soil, which is the ultimate source of both uniqueness and variety. From this perspective, the wine region is very fortunate in its location, as it was formed at the meeting point of the Great Plain and the mountainous region, along an ancient fault line, whose volcanic activity fundamentally determines its current soil structure. As the locals say, the wine region is settled on four hundred volcanoes.

This volcanic activity began approximately 14-15 million years ago, during the Miocene epoch, and ended around 9-10 million years ago. It was so varied that the rocks and their layers are virtually impossible to identify. Due to earthquakes, plate movements and the continuous transformation of rock-forming materials, the entire range of volcanic rocks is on display. This includes Miocene andesite, dacite, rhyolite and rhyolite tuff, as well as scattered rocks (pyroclasts). During the volcanic after-effects, erupting geysers created hot springs on the edge of the mountain range and in the smaller basins that had formed.

About ten million years ago, during the Pannonian period, a series of eruptions formed the dacite cone of Kopasz Hill, which dominates the landscape of the Tokaj wine region. Then, still during the Pannonian period, the Carpathian Basin sank, creating the Pannonian Sea, which covered the landscape at an altitude of about 120 metres in today’s elevation system.

Later, the Ice Age during the Pleistocene brought about intense erosion, weathering and valley formation, with various materials accumulating in thick layers at the bottom of the slopes. Strong winds from what is now the Great Plain deposited significant amounts of dust at the foot of the mountains, which has since formed loess and is now a factor in soil formation.

Despite the high degree of diversity, we can attempt to classify the soil into three main types. The most important type of viticultural soil is compact, rock-like soil, which is formed from the weathering and aggregation of igneous rocks, primarily andesite. A completely different but significant soil type is loess, which is found in many vineyards as a covering layer deposited on volcanic bedrock. The third material, formed during mechanical weathering from rock debris, highly acidic rocks and white rhyolite, is rock dust, which is not really bound, does not store water, and is not favourable for grapes during periods of frost or drought.

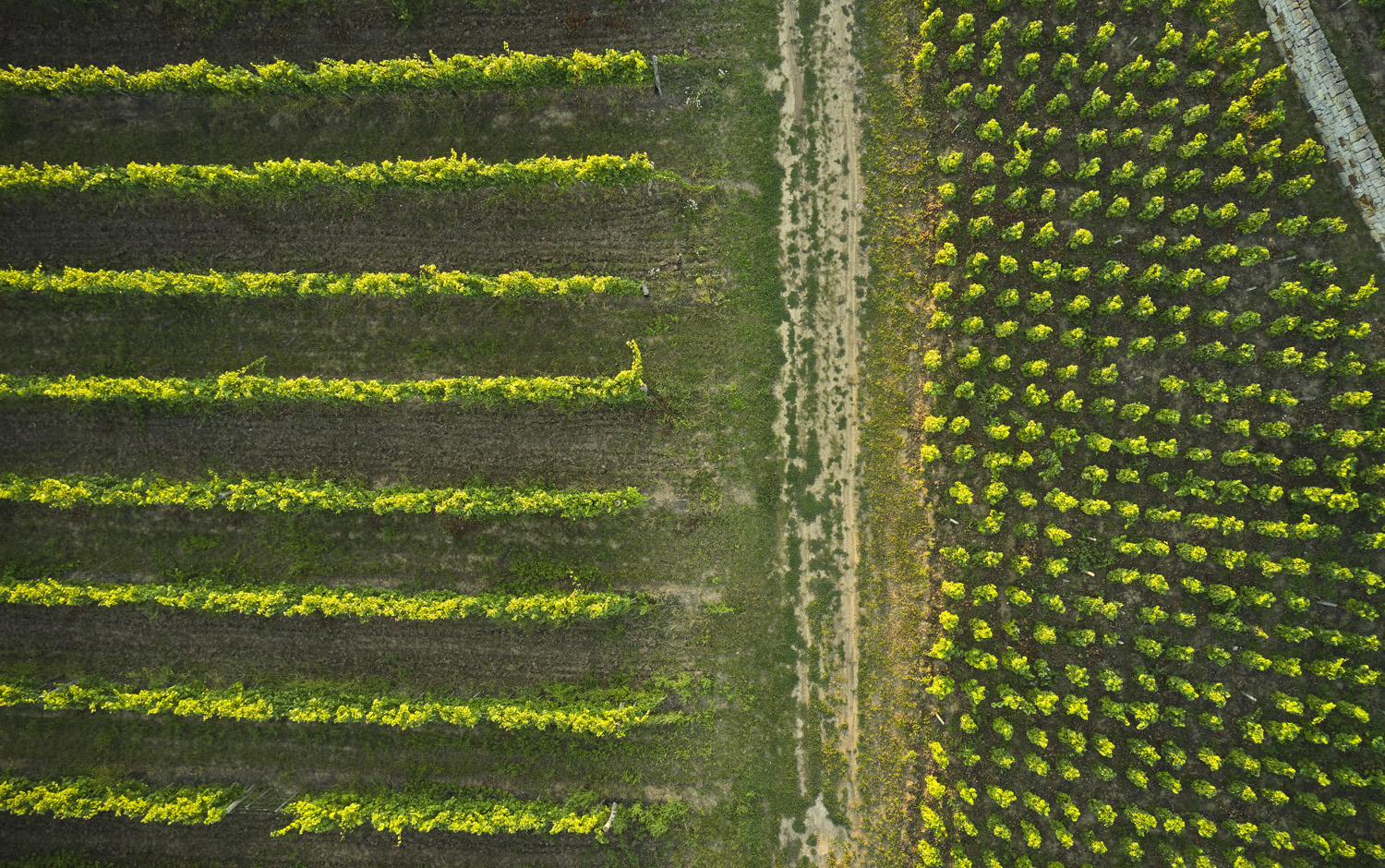

Vineyards

Kopasz Hill

The first area is the surroundings of Kopasz Hill, or, put simply, the vineyards of Tarcal and Tokaj. If you turn right off Route 37 after Mezőzombor, you can see these vineyards, which are mostly based on loess and dacite. Leaving Tarcal, the first vineyard worth mentioning is Deák, which covers around 15 hectares, but only 10 hectares are planted. Its lowest parts are around 100 metres, while the upper limit for grape cultivation is around 160 metres. Facing southwest, its main attraction is that grapes ripen beautifully here thanks to the humid heat coming from the Great Plain as well as its basin-like shape.

Heading towards Tokaj, the next spectacular vineyard on the left is Szarvas, which, covering an area of around 50 hectares, is the largest on the entire hill. It is a perfect southern slope, shaped like an open book, which helps to preserve the humid air coming from the Bodrog and Tisza rivers during the botrytisation period. In the historical classification, it received an exceptional rating above its class, obviously due to its excellent susceptibility to botrytisation. Because it was so highly valued, it was continuously owned by nobles and kings, and it is still owned by a state-owned company (Grand Tokaj) today. Its soil is thick loess that warms up easily, so the growing season here is longer than usual.

Right next to Szarvas lies the approximately 15-hectare Teleki vineyard, which is also located on loess soil and can produce wines with floral, tropical characteristics. Surprisingly, botrytisation here is only average. It has perfect southern exposure and a fairly large difference in elevation, with the roadside section at 100 metres and the highest point at 220 metres. The upper parts are quite sparsely planted.

Immediately after Teleki, before reaching the town of Tokaj, there are a group of vineyards that in 2005 were voted among the ten most beautiful wine-growing locations in the world. In common parlance, it is referred to as Hétszőlő, even though the vineyard bearing this name is only one of seven contiguous vineyards that all contribute to the view. The seven vineyards, in order, are Nagy-szőlő, Binét, Hét-szőlő, Kis-Garai, Szarka, Lencsés and Szerelmi. We will present four of these, which belong together in terms of ownership, as a single entity. The insignificant little Binét is home to the Tokaj-Hétszőlő winery estate, while Szarka has no vines. Importantly, the vineyard was practically unused during the communist era, which is why the Tokaj-Hétszőlő winery, founded in 1991, could cultivate it organically from the very beginning, later obtaining organic certification.

We are thus talking about the southern side of the 515-metre-high Kopasz Hill, which has obviously been the most valuable area throughout history. The reason for this, apart from its excellent exposure and good soil, is its ability to develop botrytis, which, as we have seen, was the most important factor in most eras. When discussing the geography of the hillside, it should first be noted that the boundaries of today’s vineyards are practically identical to those of the past. The two largest are Nagy-szőlő and Hétszőlő, which were classified as 1st class in historical classifications. The lowest point of the hillside is around 100 metres, while the highest point, at over 340 metres above sea level, is in Kis-Garai vineyard. The fourth vineyard, built on terraces, is Lencsés, which enjoys an excellent microclimate thanks to its heat-reflecting terrace walls. The soil of the entire hillside is, of course, the familiar dacite, with thick loess at the bottom and thin loess at the top. It is considered an excellent area for Aszú, although this picture is nuanced by observations from the Tokaj-Hétszőlő estate, which suggest that Kis-Garai is more suitable for producing dry wines due to its altitude and windiness, while Hét-szőlő below the Tokaj – Hétszőlő inscription and the central part of Nagy-szőlő are more suitable for Aszú. There is an average difference of one week between the ripening of the lower and upper areas, which is not surprising, as the lower part is 1-1.5°C warmer. The bottom of the approximately 10-hectare Szerelmi vineyard is located at an altitude of 100 metres above sea level, while its top is above 280 metres. It faces south-southeast and its soil is the same as that of the previously mentioned vineyards, i.e. thick, in places 15-metre-thick, loess cover on dacite bases.

Mád Basin

Mád is the viticultural epicentre of the wine region. Located southeast of the village, Szent Tamás vineyard boasts perhaps the most beautiful vineyard panorama in Hungary and is the best-known vineyard in the basin. It produces a significant number of single-vineyard wines in several styles (Aszú and dry), thus can be considered a universal vineyard. It is approximately 80 hectares in size and is almost entirely planted except for a few hectares. The vineyard is a roughly 230-metre-high cone, the southern side of which runs into the Nyulászó vineyard. The Makovica sub-vineyard is located in this part. There is another sub-vineyard in Szent Tamás, namely Fürdő, located on the northeastern side. The slopes run down in a circle from the aforementioned cone, so there is also gentle northern exposure. The slope’s lowest point is in the Fürdő part, at an altitude of approximately 140-150 metres.

The most defining feature of Szent Tamás is its mineralogy, which is characteristic on the western side, but especially so on the northern side. The eastern side is the rockiest, while the southeastern slope is the longest; these two slopes are also the warmest. The eastern side produces the most concentrated wines, due to its water management, multi-layered zeolite and heat-retaining microclimate. The soil throughout the vineyard is particularly stony and gravelly, and surrounded by red clay, which creates a brick-like red effect when exposed to water.

South and southwest of Szent Tamás lies Nyulászó (Nyúlászó in some inscriptions), another well-known vineyard producing several single-vineyard wines, where botrytisation is uncommon. The hill is actually a half-cone, with its highest point at around 195 metres, right on its northern border, where it is bordered by Szent Tamás, specifically its Makovica part. This half-cone slopes to the south, east and west, reaching 140 metres in the east and west, and dropping below 130 metres at its southernmost point. The soil in the southern part is clayey, but the most mineral-rich parts are in the east and west, and are extremely exciting thanks to their diversity. Many layers have accumulated on top of each other, with crumbled rocks in between; in this case, zeolite is also the most common. One of the hardest soil types in the vineyard is quartz debris mixed with red clay on top, hard rhyolite underneath and then a layer of white rhyolite tuff. Most importantly, there are gaps between the hard rocks where vine roots can penetrate.

Király vineyard, also considered universal, is located east of the two vineyards mentioned above. The hill towering above it, at around 380 metres, is the highest in the Mád Basin. The vineyard itself surrounds the hill in a crescent shape, and at one time covered more than 40 hectares. This figure is currently back at around 32 hectares. One of its strengths is that Tokaj Kereskedőház (now Grand Tokaj) replanted 22 hectares around the time of the political transition, so that later private owners did not have to start from scratch. The vineyard has both eastern and southern exposure thanks to its crescent shape. Its lowest point is in the southwestern corner at 157 metres, while the terraced area, unofficially known as Öreg Király, rises to over 320 metres. Producers joined forces here in 2003 to begin a large-scale reconstruction project, which has now created what is perhaps Hungary’s most impressive vineyard.

Very intense mineralisation took place here during the Miocene epoch, starting around 15 million years ago. The volcano has six eruption levels, which were discovered in the 1970s by geologists working in a mine on the western side of the hill. Several types of soil can be distinguished on it; for example, the soil in the southwestern part is hard and quartz-rich, as well as being the most compact and massive. There is an area covered with white, crumbly tuff, almost building stone quality material, at the corner of Kakasok and Betsek, indicating that there may have been a serious volcanic eruption here… At the top, in the new part, there is soft red clay, but is also zeolite and enhydro quartz. Finally, white zeolite and kaolin occur increasingly in the unplanted western part.

According to producers, Király is perhaps the most reliable, highest quality and most versatile vineyard even within Mád. This is because vine roots can easily penetrate deep into the soil structure. This, combined with the basin’s humid climate and excellent water management, make it perfect for both ripening and botrytisation.

Directly south of Király is Betsek, whose spelling is also interesting, as some sources and some eras wrote it as Becsek. It is the largest of Mád’s historic vineyards, covering more than 100 hectares, and is a large flat hill with its highest point at around 230 metres. It is directly opposite Király, and slopes gradually downwards towards the south. There are five tuff deposits here, with the sixth bordering the Király vineyard, where Király’s soil (on its southeastern side) is similar to that of Betsek. This white tuff is most dominant in the highest parts, so much so that despite its slightly northward exposure, locals consider this part the best. Overall, it produces sophisticated, well-rounded and unique wines. Importantly, it is a universal area, meaning it is excellent for all wines, from dry wines to Aszú, and is also exceptionally reliable…

There are two other known vineyards southeast and east of Betsek, namely Veresek and Kakas, the latter of which should not be confused with Kakas in Bodrogkeresztúr. The Kakas vineyard in Mád is quite large, covering approximately 50-60 hectares. It faces west, and its highest point, planted with vines, is around 280 metres above sea level, while its lowest point is 170 metres above sea level, at the junction with Veresek and Betsek.

The neighbouring vineyard was listed in the product specification as Veresek, although the name Veres (Red) had previously been used in many places. The vineyard covers an area of 60 hectares, faces west, is not too steep, and ranges from 260 metres at its highest point to around 150 metres at its lowest. The bedrock here is rhyolite tuff, and the soil is composed of its debris. It contains no iron hydroxide whatsoever, meaning the vineyard certainly did not get its name from the colour of the soil. Most of it is a 30-year-old vineyard, mostly with rows parallel to the contour lines and mostly planted with Furmint. The degree of fragmentation here is such that the rock itself is a soil-structuring factor, which is why mineral content is particularly high.

The most famous part of the group of vineyards northwest of the village is undoubtedly Úrágya. Botrytisation is rare, yet it has always been owned by aristocrats and bankers, which says a lot. Later, the first truly great dry wine made by István Szepsy came from here, changing Tokaj’s attitude towards this wine type. Úrágya stretches along the western side of Mád, directly above the last row of houses. It has a particularly steep eastern slope, rising from 170 metres to 240 metres. On its western side, however, it descends to 200 metres, where it meets the slopes of Közép-hegy and Hold-völgy. It drops to 210 metres on its south side, where it runs into the Birsalmás vineyard, which includes a 4-hectare area of scrub. It covers an area of 60-70 hectares and is characterised by extremely stony, very red clay soil, which is less than a metre above the heavily cracked zeolite bedrock.

Urbán was also previously owned by the most influential class, but today, unfortunately, most of the vineyard is still unplanted (only 10% of the 35-40-hectare vineyard is under vine), even though aerial photographs taken in the 1950s show 70% of the vineyard under vine. The eastern side of the slope is the steepest and rockiest, with a single block of vines remaining here as an enclave. Its most valuable part is the small spur extending towards the village, whose soil is already partly different from that of Úrágya above it. The stones are more rounded there, while they are flatter here, due to repeated volcanic activity. To revitalise this area, some wineries have already done a tremendous amount of work on the eastern side of Urbán, building retaining walls from the incredibly rocky soil. Piles of stones, several metres high, were removed from the ground during preparations for planting. The soil is red and yellow clay at the top, followed by a very dense but highly weathered zeolite layer below. It contains quartz tuff that is light in colour and white on the inside because it does not contain iron, unlike the tuff found in Szent Tamás. It also contains many fossils and complete petrified tree trunks.

South of Úrágya lies Birsalmás, which covers an area of over 10 hectares and is practically entirely south-facing, with a slight western slope. The road leading to Tállya is quite steep, barely 150 metres above sea level, rising to an altitude of around 200 metres in less than 250 metres. The soil is red clay and zeolite.

The Közép-hegy, Hold-völgy, Sarkad and Őszhegy vineyards are located to the west of here. All boast excellent characteristics, but none of them have yet achieved real fame. Perhaps the best known is Hold-völgy, which stretches from Mád to the village of Rátka, forming a crescent. Its area is around 60 hectares, it faces roughly south, and its soil is compact quartzite rhyolite that does not crumble easily. It also contains iron hydroxide, which gives it a slight reddish tint that is also visible on the surface. There is also a more compact, clayey component, which is undoubtedly responsible for the particularly deep tones found in its wines.

Danczka is located southwest of Mád and covers an area of more than 200 hectares. It is nothing more than a 160-metre-high, bread-shaped hill, the southernmost point of which descends to a height of around 100 metres. The topsoil is quite thick, reddish-brown, extremely sticky clay, which is not very exciting in itself, but recent excavations have shown that it exhibits a high degree of variability: it contains black, white and red quartz, andesite and tuff. A special feature of Danczka is that it is the vineyard which has always produced the highest sugar levels and also has excellent botrytisation potential.

The soil structure of the Rátka vineyards is very similar, with the Hold-völgy and Közép-hegy vineyards also extending into this area. However, the two best-known vineyards are Padi-hegy and Isten-hegy. The two vineyards are actually two merged hills that form an inverted heart shape. The entire western side is covered by the Isten-hegy vineyard, which covers approximately 50 hectares, with its highest point at over 170 metres and its lowest point at around 130 metres. The soil in the southern part of the vineyard is clay mixed with some calcareous sediment, gravel, crushed quartzite, opal and jasper, while there is zeolite in the northern part. The highest point of Padi-hegy is over 200 metres above sea level. Quartzites are more commonly found at the top of Padi-hegy, but there are also traces of obsidian. The rock is quartz-rich and hard on the western side, while there is yellow or red clay with a reddish tinge, suitable even for brick making, on the south-southeastern side. Traces of a geyser vent, evidenced by a large layer of bentonite soil, can be found in a clearly defined area of the southern part.

The deepest part of the Mád Basin, namely Tállya and Abaújszántó, is extremely interesting but still relatively undiscovered. The two villages are connected by a ridge stretching from northwest to southeast, so most of the vineyards face southwest. The soil here is also rhyolite and rhyolite tuff, and the quality of the vineyards is mainly determined by their altitude. Locals consider Bátorka, Kis-Rohos, Nagy-Rohos, and Hasznos, which is mostly south-facing, to be the best. However, nowadays there are hardly any vines growing in some of these areas.

The Mád Basin does not end geographically at the southern border of Mád; the vineyards of Mezőzombor, Bodrogkeresztúr, Bodrogkisfalud and Szegi, either in whole or in part, should also be included. Leaving the roundabout on Route 37, you immediately see an impressive group of vineyards on the left, owned by the Disznókő Winery. If you look at the entire contiguous area, you can see that it is defined by three eruption points or geyser cones. The northernmost one is Harcsa-tető, followed by Király-tető (not to be confused with Király in Mád) after a small valley to the south and then Hangács slightly to the east. The largest part of the vineyard group is the Dorgó vineyard. Its lowest point is near the roundabout, at an altitude of 110 metres above sea level, while the highest, terraced part rises to over 200 metres. It mainly faces west and, to a lesser extent, south.

Kapi is a famous vineyard that has produced single-vineyard Aszú wines in several vintages, and its history is closely linked to the Lajosok and Hangács vineyards. Hangács has darker soil containing more clay and large pieces of rhyolite, while Kapi and Lajosok have looser, loam-like clay with layers of loess and calcareous deposits in many places, as well as rather crumbly rhyolite tuff. However, it is important to note that these vineyards differ much more in terms of altitude than in terms of the character of their wines, which means that the upper part of Kapi differs more from its lower part than, say, the upper part of Hangács. The lower-upper distinction also applies to botrytisation. Botrytis is more prevalent in the lower parts, producing large, deep-coloured berries, often with entire clusters affected by botrytis, while small, purple-red berries grow in the upper parts. Kapi, Hangács and Lajosok are also south-facing vineyards overlooking the Great Plain, protected from the north by the ridge, with very good botrytisation potential, meaning they can be considered universal vineyards.

Continuing along Route 37, you will soon reach the “other” Kakas vineyard, which covers an area of approximately ten hectares. It faces southeast, is not steep, and the section along the road is 120-130 metres long, with its highest point at 180-190 metres. It is particularly interesting in terms of its microclimate, as despite its warmth – perhaps due to the protection of the forest and the hilltop – the wines produced here have lower alcohol and higher acidity. Its soil is particularly unique, as rhyolite tuff is relatively heavy and dense, with medium fragmentation. The top metre of soil is compacted, but underneath there is cracked rock that the vine roots can easily penetrate.

The next vineyard along Route 37 is Kővágó, which covers approximately 50-60 hectares with excellent southeastern exposure. This is followed immediately by Lapis, which owes its reputation primarily to its Aszú wines. This is no surprise, as the proximity of the Bodrog River ensures adequate humidity during the September-November period. Lapis also faces southeast, with vine rows perpendicular to the slope, open and well ventilated, and clearly a grand cru area even at first glance. It does not have uniform characteristics; most of its approximately 130-140 hectares has a very slight slope, only rising 30-40 metres over a distance of about 800 metres from the road. This part is called Nagy-Palánt and Kis-Palánt, but these two names do not appear as official sub-vineyards. The next section does not have a specific name, but it is steeper, while the uppermost row of plantings is Lapis-tető, which boasts spectacular terraces and a slope reaching 25%. Mention should also be made of the small sub-vineyard called Halas, located in the vineyard’s western corner.

Lapis also rests on rhyolite tuff foundations, but its topsoil is grey and brown clay, which is much denser and has fewer inclusions. Perhaps it is the compactness of the top layer that makes wines from Lapis so austere and so characterfully and highly mineral that many consider them almost aggressive. As mentioned above, Lapis has been classified as an Aszú vineyard for the time being but can produce outstanding wines of all types, thanks to its balance, structural depth, complexity and elegance, which it can, moreover, deliver practically every year.

Right next to Lapis is Vár-hegy, which covers an area of 30-40 hectares and stretches from east to west. You could say that it surrounded the hill from the south if it weren’t for the 10-hectare Kisvár vineyard next to the road. Vár-hegy was a relatively active volcano, as can be seen from its soil structure; exploratory drilling did not even reach the bottom of the tuff layer, and the hill is dotted with lava flows and volcanic bombs from multiple eruptions. The topsoil is a mixture of weathered tuff and brown forest soil formed from erubase soil.

There is another well-known vineyard on the hill, the Barakonyi, which covers only seven hectares. It faces southwest, with a small ridge in the middle, so there is also a small southeast side. Its height ranges between 170 and 240 metres, its surface is relatively eroded, and its humus content is quite low, so the vines are forced to work hard. The bedrock is similar to that of Vár-hegy, but the patches are very diverse, so the wines produced here are particularly serious, yet elegant, with lively minerality.

From Erdőbénye to Sátoraljaújhely

The Erdőbénye Basin reaches the Bodrog River at the village of Olaszliszka, and the first thing you notice is a foothill. There are more than a dozen well-known small vineyards here, but the real gems are further in, around Erdőbénye. The most famous is undoubtedly Lőcse, which sources note was owned by the town of Lőcse (now is Slovakia) from the mid-18th century. The 15-hectare vineyard faces southwest and has pure rhyolite soil enriched with a considerable amount of obsidian. The neighbouring Omlás is a relatively large plot of land, covering around 30 hectares. It faces south and its soil consists of perlite-pumice rhyolite tuff debris covered with erubase soil. To the east of Tolcsva, you can see three ridges, the first of which begins at the Petrács vineyard and runs down the western side of the vineyard. The approximately 100-hectare Szár-hegy already belongs to Sárazsadány. It is actually the third ridge, whose southern exposure slopes in two directions, east and west. The soil is exceptional, with minimal humus content on the surface, consisting entirely of rock debris, malachite and jasper conglomerate.

There is an exceptional row of vineyards above the road connecting Erdőbénye and Tolcsva, which runs for 2-3 kilometres up the hillside, covering it from about 150 metres to 250 metres, the best-known of which are Budaházi, Szentvér and Mandulás.

The third inverted V shape of the wine region begins at Bodrogolaszi and reaches its deepest point at Sárospatak, where the village of Makkoshotyka is located at the tip of the V. There is a hill called Gombos Hill in Hercegkút, boasting a vineyard which the product specification calls Gombos-hegy., there are two large hills north of Sárospatak, the (newer) around 250-metre-high Király Hill and the 300-metre-high Megyer Hill. There are relatively large vineyards of the same names on the southern sides of both, i.e. Király-hegy and Megyer-hegy, covering an area of more than 100 hectares.

Sátor Hill, located west of Sátoraljaújhely, is exceptional but less well known. It rises to a height of 420 metres and continues westward, after a col, into Fekete Hill, which is 100 metres lower. Of course, these two hills are also volcanic in origin, covered with dacite cones and erubase soils. Vines here climb to a height of 250 metres, found in vineyards such as Fekete-hegy, Szemszúró, the aptly named Köves-hegy, Vióka (from which there is already a single-vineyard wine) and the renowned Oremus.

Origin protection

The history of Tokaj’s designation of origin began in 1737; however, the product specification, which became the cornerstone of modern winemaking, was only finalised in 2012. Since then, no fewer than ten amendments have been published, which are not easy to keep track of. On top of that, due to the situation in the wine region, every amendment is accompanied by heated debate.

The cornerstones of the 2012 regulations were the six permitted grape varieties (Furmint, Hárslevelű, Sárgamuskotály, Kabar, Kövérszőlő and Zéta) and eight wine types: white wine, late harvest wine, Aszú (3, 4, 5, 6 puttonyos), Aszúeszencia, Eszencia, Máslás, Fordítás, Szamorodni (dry and sweet) and sparkling wine (which may only be traditional method). The necessary analytical and production rules were defined for each of them, while more than a four hundred vineyards were demarcated. Single-vineyard wines must be 100% vintage, origin and variety specific.

An important change came into effect in 2013: the Aszúeszencia wine type and Aszú puttony numbers were abolished, although the latter requires a little explanation. From then on, wine labelled as Aszú must have a minimum of 120 grams of residual sugar; however, winemakers could still indicate the number of puttonyos, except for 6 puttonyos, which could only be used for wines with 150 grams or more residual sugar. Since then, besides minor technical modifications, in 2020 the minimum sugar content of sweet Szamorodni, Máslás and Fordítás wines was increased from 45 to 60 grams, and the bottling of Aszú in larger bottles (magnum, etc) was permitted.

Events

Domestic and international wine programs